Discussing all aspects of genealogical research, documented family tree building and DNA results from various consumer companies.

Sunday, November 16, 2025

Free Virtual Event: "The History of the Acadians: Through Tranquility, Turmoil and Tenacity", presented by Nicole Gallant-Nunes

Thursday, December 12, 2024

The Acadian Expulsion Memorial List Project, Part 2 - Published 13 June 2025 by Nicole Gallant-Nunes

I’ve just released Part 2 of my Acadian Expulsion Memorial List project. I released Part 1 six months ago on 13 December 2024 with just over 2,400 names added. I have added 2,500 more names totaling over 4,900 names for Part 2, published 13 June 2025.

Here are the links to Pat 2 of the project spreadsheet, available in Google Sheets and Microsoft Excel.

Google Sheets: The Acadian Expulsion Memorial List Project, Part 2, Google Sheets

Link to Microsoft Excel: The Acadian Expulsion Memorial List Project, Part 2, Microsoft Excel

I wanted to provide some information about the project and explain a bit about the process of adding these names. I apologize that this is in English-only as I am unfortunately not fluent in French as I was born and raised in Massachusetts. I can read French but can’t speak it or write it well enough to translate so I apologize that there isn’t a French version at this time.

I began this project in September of 2024 and my main goal was to list the names of the Acadians who sadly passed away during the period of the Acadian Expulsion. I recorded a 2 hour long video to accompany the release of Part 1 of this list that I published in December of 2024 that explains all of the information you may want to know, if you don’t already, about who the Acadians were, where they settled and all about the events leading up to this expulsion so I recommend checking that out so you will know the more of the backstory of these events. The link to that video hosted by the Have Roots Will Travel YouTube channel is available right at the top of my Memorial List when you open it up in Google Sheets or Microsoft Excel. A link is also available here: The Acadian Memory Project, Have Roots Will Travel YouTube Channel

The period of the expulsion is generally recognized as starting in 1755 and ending in 1763 following the Treaty of Paris. After this, Acadians were free to relocate from the location they had been exiled to. These places include the U.S. colonies along the east coast, England, France and even from being detained inside of Acadia such as at Halifax. Most were looking to resettle in French Territories and presumably trying to locate their family members they may have been separated from.

The next few years between 1763 and 1767 included a lot of moving around for our Acadian ancestors. We can see distinct migrations happening from certain areas to another, such as the Acadians in Halifax went on to settle in Louisiana, the Acadians in England went on to settle in France, the Acadians in Massachusetts went on to settle in Quebec and the Acadians in Connecticut went on to settle in St-Domingue (Haiti). Not everyone resettled in the same place but just to give some examples.

After 1763 wouldn’t generally be considered part of the expulsion period as most Acadians were now considered free subjects, however there were extensive losses of Acadians even after 1763, especially soon after arriving in new locations. Louisiana, French Guiana, Haiti and Quebec saw significant losses as Acadians landed in these new areas. This continued even until 1785 when Acadians from France were attempting to settle in Louisiana, nearly 20 years after the early groups of Acadians arrived there. There were even still deportations happening to the Acadians in St-Pierre and Miquelon which were French territories just off the coast of Newfoundland. The Acadians there were deported multiple times to mainland France and many did not survive. This was happening in the 1760’s and 1770’s.

So when I went about compiling this list, I didn’t have a set criteria in mind when it came to specific years or locations. I kind of went with my gut and if I felt that this persons death could have been a direct result of the expulsion, they were included. This criteria may change over time as I edit the list, but this is how I have done it so far. I tried to take certain factors into consideration, such as knowing that the infant mortality rate was already high during this time period to begin with. Most couples had several children and it’s uncommon to find a family that didn’t lose at least one child young even before the hardships of the expulsion, so it’s tough to say if a child who died during this period was simply an expected infant mortality loss or a loss as a direct result of hardship. Either way, they were included just in case.

I also took into account how long someone was living in a particular area before passing away. Let’s say someone arrived in Quebec in 1755 but didn’t pass away until 1763. I might look a bit deeper into that person, more than just their year of death, and I would look at their age. Were they already in their 60’s or 70’s and could this have just been a natural death due to old age? Or were they 15 years old when they would have been out of that ‘danger zone’ of the expected childhood loses and by all accounts should have survived until adulthood had they not experienced the physical and mental trauma of the expulsion that may have hastened their demise? I took that into account. I also look at the children lost, again keeping the infant mortality in mind but also considering the physical and mental trauma the mother would have experienced. Did the events of the expulsion impact her ability to develop and nourish a healthy child? In some cases I saw losses of several children in a row during and following the period of the expulsions. If that mother had remained in Acadia, living her normal life, would she have had 6 children perish young? Hard to say, but those children are noted just in case.

So how did I go about finding the people whose names are listed? Ideally we want to find a burial record and in a lot of cases we do have those but in most other cases we don’t so I had to rely on other records to help figure out if they were still alive at a certain time. There were censuses taken in Acadia, such as in Grand Pre and the Beaubassin area that let us know if someone was living at that time. I then tried to find them on subsequent censuses or records. For example, we know that the Acadians around Chignecto were sent to South Carolina so I checked those records upon arrival in 1755/6 and then again in 1763 to see who was still present or who was lost. I did this for each location that the Acadians were exiled to. I used a variety of sources, which I’ve cited at the bottom of my Memorial List, in order to try to pinpoint particular years and locations where our ancestors were. I also used the records of family members to help, such as if a spouse remarried by a certain date, if a child married and listed her parent as deceased on that date, the burial record of a spouse or child that may list their family member as deceased. All of those are examples of other ways I tried to determine a particular person was alive or not at certain times and I did this for each person on the list.

When I published Part 1 I was asked a few questions that maybe others were thinking as well so I figured I would mention them. The abbreviation NFI that you will see in the Notes section stands for No Further Information. It just means that this person has disappeared from paper trail records at the time of my current research. As I keep researching, I may find a burial record for them somewhere that I’ve overlooked or I may find them alive and well in another location 20 years later so the list will be edited as needed as I conduct more research. NFI just means for now, I don’t know what happened to them during the expulsion period.

The different columns of the list are pretty self explanatory. It’s the name of the person who died (or likely died) and the name of their spouse, or spouses, and their marriage year. Then the name of their parents and the parent’s marriage year. Followed by their date of birth or baptism. A lot of these birth years are estimated based on subsequent records such as censuses or burial records where an age may be provided. They are not always accurate, but more of an estimation. When a specific date is noted that means there was a baptism record found for them mentioning their date of birth. Then a column for their location of birth or baptism.

Their last known location in Acadia is the next column. Again, I would primarily use census records for this information or even perhaps a baptism, marriage or burial record of a family member that puts them in a specific location at a certain time that I can reference. If we know they died at sea in 1758/1759 en route to France then we know they would have been in Prince Edward Island or Ile Royale in 1758 so that’s how I determined that. There are still plenty of gaps in my research where I haven’t figured out exactly where someone was just prior to the deportations. That may be because I couldn’t find them on any records or simply because I didn’t have enough time to research that aspect of their lives prior to Part 2 being published. At some point I will go back and try to fill in all those gaps but I ran out of time for this publication as I’m having shoulder surgery in a couple of weeks and won’t be able to use my arm much for at least the first month of recovery so I will follow up with a Part 3 in the future which should tie up any lose ends I can.

The next column is their date of death or burial. If the exact date is known from a burial record or even a declaration made by a family member and recorded later on, that would be where that information came from. If it’s a generalized date then I based that on the availability of other records, such as the censuses and family members records that I mentioned before. It we know they died sometime between 1755 and 1763, I would note that.

The next column is the location of death. If it’s known, it’s noted, if not I may have written “likely died in Quebec” and that would be based on where their family ended up or other factors such as the general movement pattern of folks from a specific area to another such as those at the refuge camp Camp d’Esperance, they mostly went on to Quebec. We know that most of the Acadians on Prince Edward Island and Ile Royale were sent to France although there were quite a few who left the area in 1756 and 1757 and headed for Quebec so those patterns are considered as well. If the location is noted “Unknown” then that means there were no further records found in a specific area and we just don’t know for sure what happened to them. It’s the same for the date of death column where it may say “died 1755+” which just means “died sometime after 1755”. They would have been found on a census in Acadia and then disappeared from further records so their fates are just a mystery and hopefully someday we can learn more about their stories.

The next column is the Notes section. I used this section to note other family members who had perished because it really shows the impact the expulsion had, especially on the Acadian community as a whole, but really focusing on each individual family. There were some entire families that perished. Both parents and several children in one fell swoop. Absolutely heartbreaking. So that Note section is important for showing the impact and possibly explaining a bit about how their year of death or location of death was estimated.

The final column is new to Part 2 that I didn’t include in Part 1 but is incredibly helpful. This last column provides the WikiTree ID number for each person listed. These profiles are managed by the Acadians Project on WikiTree and all the information you may want about each person, including the sources and records for them, will be on each profile so you just type in the WikiTree ID and you can have access to what us Acadian researchers have. I think that is so important because a lot of you will want to see the actual records, when possible, and learn even more information about each person that my list wasn’t able to incorporate so I highly suggest checking out the profiles.

I added information to thousands of profiles as I worked through my list and also created hundreds of new profiles so if you haven’t looked at your ancestors profiles recently, be sure to check for updated information I may have added. I can’t thank Gisele Cormier and Cindy Bourque Cooper of the Acadians Project enough. They were so kind and generous through this whole process...to help me locate records or just to get a second, or third!, set of eyes on a family I was researching that was driving me crazy with my mind going in circles, they are so great to collaborate with. They created a category specifically for my Memorial List so everyone added to my list will be added into that WikiTree category so all the profiles can be found in one place online which will be so helpful. The Acadians Project is a wonderful team of researchers and genealogists who go above and beyond to make early Acadian research accessible to everyone and that is so amazing. I’m very proud to be part of that team.

Finally at the bottom of the list you will see a section devoted to the statistics of the losses. I counted up how many people died in each specific location and I estimated the average age of death based on the people I have listed so far. That averaged age is just 24 years old. It’s incomprehensible to think of how many young Acadians were lost. I also think it’s important to see how many people died in a specific area.

Who is who is not represented on the list? There were many folks who we just don’t know what happened to. For example this includes children who could have been born after the 1752 census in Prince Edward Island and then died at sea in the sinking of the ships the Duke William, the Violet or the Ruby and therefore there’s no record of them at all as a lot of baptism records from that time were lost or destroyed. There must be hundreds if not thousands of them who were completely unaccounted for but we figure must have existed as we know that a few children could have easily been born in each family in that 6 year gap, but we just don’t know.

Also not included on the list are folks who were last recorded on the censuses in 1763 and then disappear from records elsewhere. I am still researching those who fall into that category and will likely add all of them in later as I research further but for now I haven’t made note of them. Those would be the folks who were last recorded on say the 1763 census in Massachusetts for example, and then seemingly vanish. A lot of Acadians in Massachusetts in 1763 moved on to Quebec in the next few years so you would expect to see them in records there. Maybe their children would be baptized there or marry there mentioning their parents? Maybe we would find a burial record for them? But sometimes they just vanish so it’s possible they died just after 1763 or it’s also possible that the search engines I use to try to find them doesn’t have their name transcribed quite right and maybe the records don’t pop up during a search. It could be that simple. So the research into those disappearing people is ongoing.

For the most part I really tried to focus on the 1755 to 1763 time period and then also focused on transition periods such as 1763 to 1767, among others, that I felt were connected to the expulsion events. Had they not been deported in the first place, they wouldn’t have had to relocate in 1764 and perish in say Haiti, if that makes sense. So they were included.

In Part 1, published in December 2024 I had 2,408 names added. For Part 2 published in June 2025, I now have 4,936 names. I could have added more but again I ran out of time before my scheduled shoulder surgery so I will pick back up on the research in a few months when I’m able. You’ll see that some people don’t have a WikiTree profile yet and that’s just because I ran out of time and didn’t get a chance to create one yet. I really want to further my focus on the families in Ile-Royale and Cap-Breton and the Acadian families of Newfoundland that don’t get as much research attention so I started to research and document them in Part 2 and will continue to do so when I can.

So that’s the brief explanation of the project and how I compiled this list. Again, it’s going to be edited over time as more research is done and hopefully as more records are found to provide some closure to the lives of these wonderful people.

I really wanted to have the names of those lost listed in one place, to aid in research of course but also to be a kind of memorial for our cousins who were put through unimaginable devastation and without whom we wouldn’t be here today so now we can say their names to honor them and we will remember them always.

If you have any questions as you are looking through the list or watching the video for Part 1, please reach out. You can message me on Facebook or email me. I added my contact information on the list. Additionally if you come across any errors or know of a source for different information, please let me know. I’m always around and would love your thoughts and feedback.

Vive l’Acadie!

________________________________________________________________________________

Sunday, October 13, 2024

acadiann.substack.com collaboration articles with fellow Acadian researcher and many-times cousin Ann G. Forcier, 2 June 2024 and 13 Oct 2024

Acadian endogamy:

Are you my cousin?

Remember the children’s story

Are You My Mother? (P.D. Eastman)?

In it, a bird hatches while its mother is off her nest. The chick then wanders about among other animals, vehicles, and machinery until a steam shovel drops it back in its nest, and the mother bird returns with the hatchling’s first meal.

That would be the template for my own imagined Acadian story: Are You My Cousin?

I’d be the bespectacled, blond-haired guy who’s raising his arms because someone from the other side of the room blurted out a name that was in my family tree.

I did that once at a poetry reading. My now writing pal — and founding member of Acadiann — George Comeaux read a lilting poem in his soft southern drawl. When he finished, I said something in French. Which completely befuddled him because, by his generation, the Acadian was there only in English. (Through the years, we’ve identified our common founding ancestors as Pierre Comeau and Rose Bayon.)

When I try to figure out what cousin level we are, that’s when I run into the realization that I don’t have a family tree; I have a family thicket. We have so many lines and sidelines in common as to remind me of the song I am my own Grandpa.

By way of example, let’s say George and I are related 10 times in 10 different ways. Are we closer cousins than we think based on Pierre and Rose 12 generations ago?

At this point, I need professional help.

Fortunately, Nicole Gallant Nunes is there. She’s a professional genealogist who often wrestles with the Acadian Question.

Nicole: It's a constant game of "Hmm, are you really 4th cousins or do you just share a ton of ancestors further back making the DNA connection appear closer than it technically is?" Some of them are just impossible to figure out without solid paper trails because of all that redundant DNA we share with our matches many, many times over. It throws everything off!

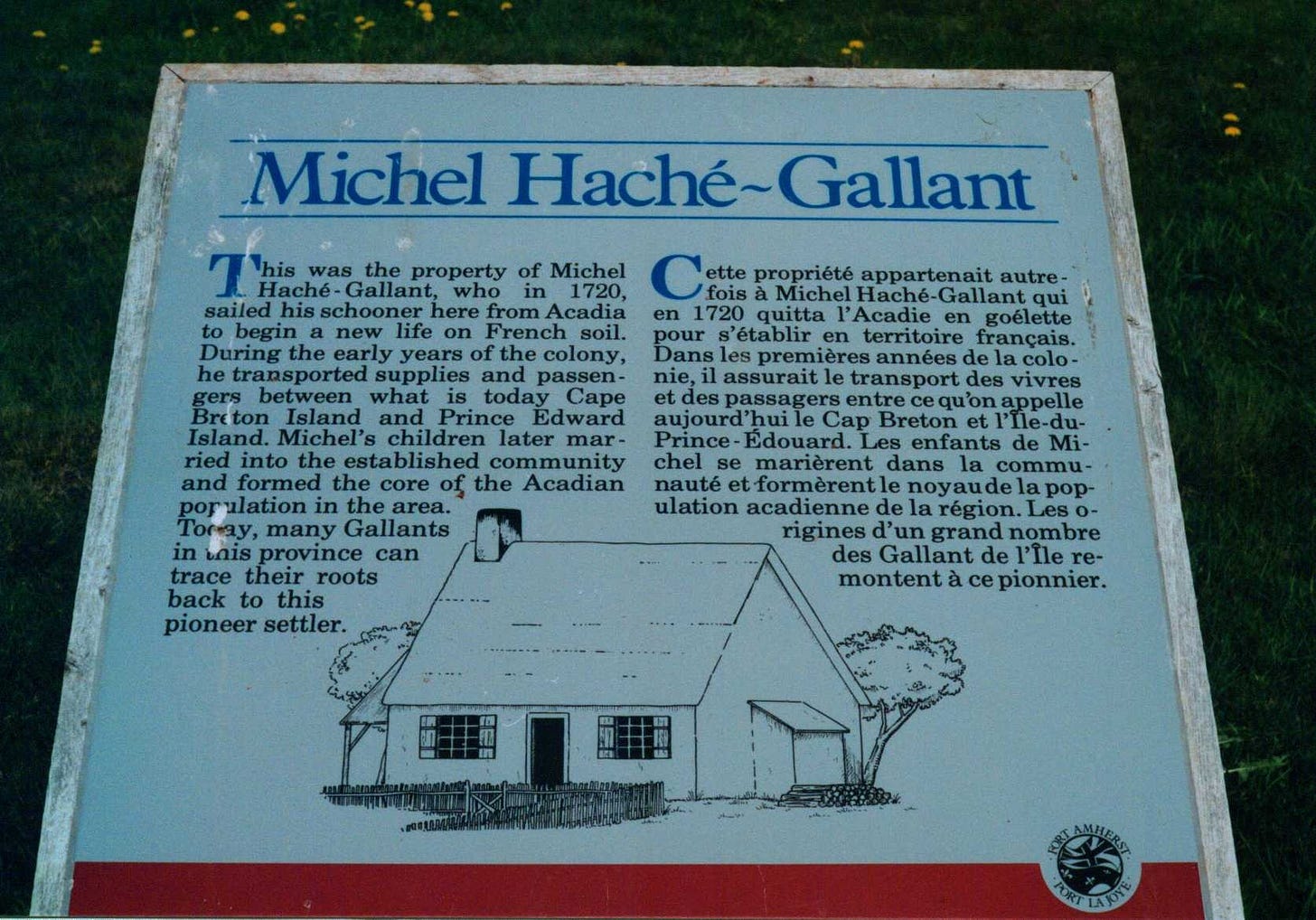

I touched on endogamy and pedigree collapse briefly in my article about Michel Hache Gallant because I was getting so many questions about how we could still have a genetic tie to Michel all these generations later and it's absolutely because of endogamy.

Acadians in general will share like 75% of their ancestors with everyone else of Acadian descent. I'm not sure of the exact statistic, but you catch my drift. It's a ton (lol) and it just keeps getting reinfused and doesn't have a chance to 'die out'.

Acadiann: So much for the British guys who thought they’d destroy Acadia through assimilation and separation.

Nicole: Ha! They clearly underestimated the incredibly interwoven and resilient bloodlines of the Acadians.

When it comes to Acadians in particular, we will share many ancestors with each other, much more than the endogamy and pedigree collapse that is common in French Canadian lines. Quebec is endogamous for sure but Acadians are on a whole other level. We definitely are our own Grandpa (haha).

Genetically we are very similar and it tends to show in our DNA as we inherit many short chunks of DNA from our shared ancestors, more so than the longer stretches of DNA most people have. I tried chromosome mapping many times on Acadian DNA and it's just a mess to try to figure out what bits came from which ancestors because there are always so many in common.

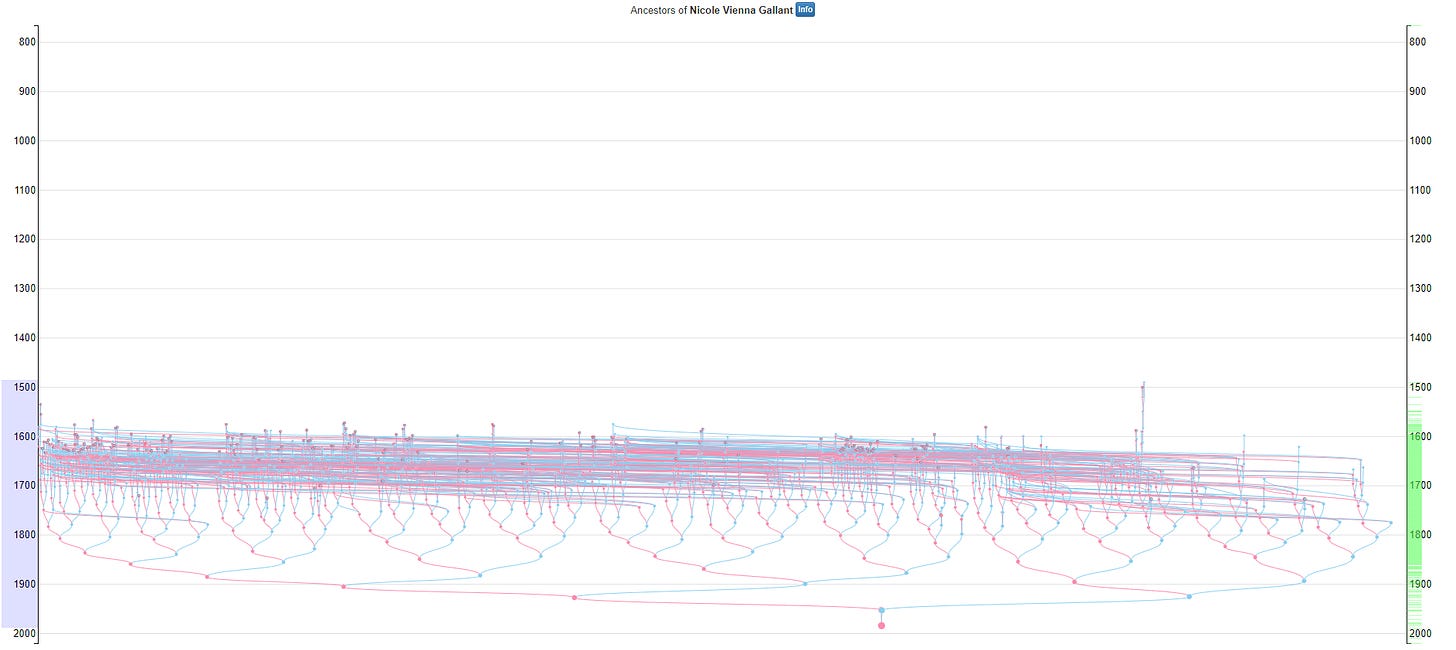

This my own endogamy image for my paternal tree. You can see that paternal grandma (Quebecoise) represented by the pink dot has a lot more individual ancestors than my paternal grandfather (Acadian) represented by the blue dot. The endogamy is much more rampant on the Acadian side but is still very prevalent in French Quebec for sure.

It's incredibly common to descend from an ancestral couple several times. So far my record is descending from six children each by three different couples, one couple being Acadians Antoine Bourg and Antoinette Landry. I also descend from six children of Pierre Michaud and Marie Ancelin, and from Jean Pelletier and Anne Langlois in Quebec.

Acadiann: Then, I suppose, it’s not so odd that someone thought my brother looked like a Gallant after about 250 years post-Grand Dérangement (Digging in their Basement).

Nicole: I remember years ago I was trying to map out how many actual individual ancestors I had. You know, like how you are supposed to have 4,096 ancestors at 10x great-grandparent level? I had a minuscule fraction of that amount on my Acadian side. It was like 100 unique individuals at the 10x generation and that's just with one Acadian grandparent. Can you imagine the tangled web of someone fully Acadian or Quebecois? Whew!

Acadiann: Reminds me of something I heard recently at the American Canadian Genealogical Society virtual conference on DNA. Genealogist Debbie Wilson Smyth’s workshop was titled “DNA Doesn’t Lie, But It Needs Help to Find the Truth!” She told us that we have both a genealogical tree and a genetic tree, that the genetic one is a subset of the genealogical one.

I wonder when someone says there’s a “false match” because of endogamy, whether that’s factual but not true. It’s a matter of perspective, right? If I share more genetic material with a double 4th cousin than a second cousin, then we have a closer genetic tree right? Even though I have a closer genealogical tree with my second cousin?

Nicole: Exactly. It will vary from company to company but Ancestry in particular uses the Timber algorithm which is designed to disregard parts of our DNA that they believe is passed down from a common genetic group from the same area (like Acadians) versus it being a true match with that segment passed down from a shared ancestor. So when Ancestry removes those pieces that match because they don't think they are true matches, it's helpful for most people to eliminate that 'noise', but, we aren't completely sure how it affects populations that have a lot of proven endogamy because those removed pieces could actually be true matches for us, but possibly further back in our tree that may not be able to be discovered with paper trails.

Acadiann: So when I try to figure out what kind of cousin George and I are, or what kind of cousin you and I are, I can use paper documents to trace our genealogy, and DNA tests to trace our genes, and I might come up with different answers? And they’d both be true?

Nicole: Yes, both answers would be true despite the difference. Paper trail genealogy may show you that your closest shared ancestors are your great-great-grandparents, technically making you third cousins, but if you were to look at the shared DNA, you may show a closer relationship appearing as possible second cousins due to all that inherited DNA from earlier shared ancestors. This makes genetic genealogy tricky for people with endogamous roots. We are learning more about how to tackle these challenges as the field progresses but the possible inflation of shared centimorgans should always be considered when trying to piece a DNA match into your tree with known endogamy.

Acadiann: Perhaps a better model than Are You My Mother? would be Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet 43, first line How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Ways. For Acadians, it would be How Are You My Cousin? Let Me Count the Ways.

Nicole: This is so true! I have yet to meet another fellow Acadian or French Canadian that I do not share at least one ancestor with.

I believe that's what makes Acadians so amazing. We are so in touch with our history and we tend to treat everyone like family because, well, we are just one giant, extended family.

Resources

Strategies for Overcoming Endogamy Nicole Elder Dyer talks about Marie’s Acadian and French-Canadian lines to explore this concept

The genomic heritage of French Canadians For those with a science-geek bent. When it comes to medical genetics, so says the author, an Acadian is not interchangeable with someone from Montreal

Acadian Ancestors and Their DNA “When I first discovered my Acadian heritage, my now-deceased cousin Paul LeBlanc told me that if you’re related to one Acadian, you’re related to all Acadians. I thought he was being facetious, but when he sent me a list of 137 ways we were related, I quickly realized how intermarried this isolated group of people had been.” Roberta Estes

Genealogical vs. Genetic Family Trees

About those British guys - Patrick LaCroix’s series on Acadia under British rule

https://querythepast.com/british-acadia-beginnings/

https://querythepast.com/british-acadia-french-neutrals/https://querythepast.com/british-acadia-unraveled-deportation/

Link to original substack article: https://acadiann.substack.com/p/acadian-endogamy?fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR1y92MeiUnybbzPs7HLad628jCSEoLd8qF6SFRXi22pMF5eFkWpE2DujIg_aem_ARGKAbzHJ4obSlYjL-tzwDVs2qk2nZa_rYcqeuETtN0eLEb7G9d7gF6_WPc0zjkwH1h_dBE_EHtLhSxfuX8Bbfri

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

The trauma of the expulsion of Acadians, Part 1:

Empathetic witnessing

*Spoiler alert: the destruction of the Acadian culture and people was unsuccessful.

“Trauma is not what happens to us. But what we hold inside in the absence of an empathetic witness.”

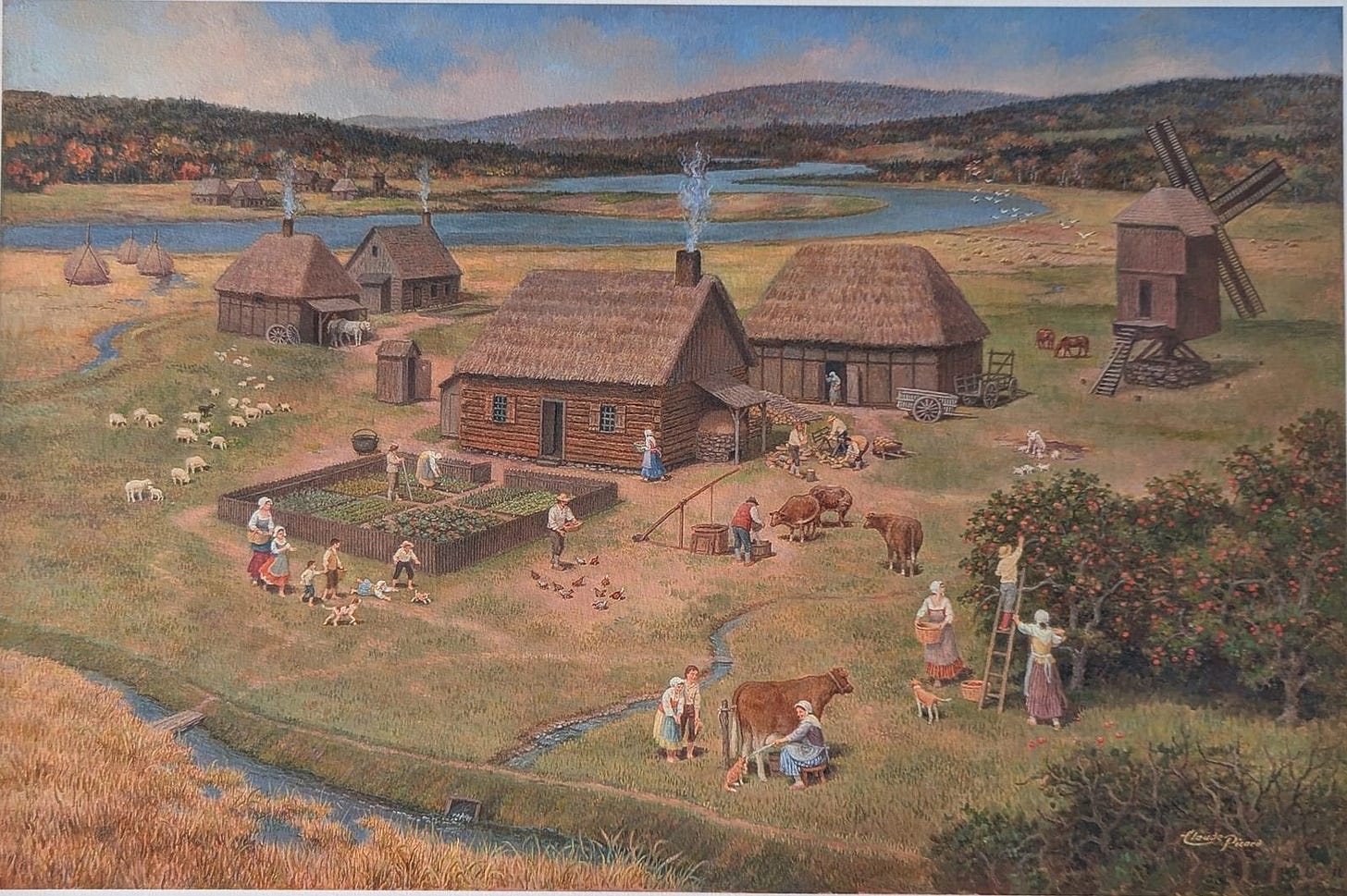

print of a painting by Claude Picard (Acadiann’s collection)

Imagine — you are the masters of your communal destiny. You spin, sew, garden, farm, hunt, fish, preserve, carve, build, sail, herd, play, fiddle, tell stories, chop wood, bundle hay, gossip, laugh, cry, birth babies, raise children, make love, loom cloth, buy imports from France and the English colonies, trade with your Mi’kmaq neighbors, look out on the marsh and sea and feel blessed. Despite the cranks in the village. Or maybe because of them. Soldiers and overlords are more nuisance than impediment.

19th century print, unknown artist

Imagine — you are ripped from your land, separated from your family and neighbors, watch your homes burn, your gardens trampled, your livestock slaughtered. You have only what you wear. You are frightened, too frightened to cry or rage. You may be able to hide behind your Maman’s skirts. Or speak the language of the invaders to ease the terror of your loved ones. Or set aside your cares because the times call you to lead your band of survivors through territory unfamiliar to you and among people you don’t understand. You have little to no means to provide and protect. Or you wonder why your Maman and Papa look like your Maman and Papa but don’t act like them. You land in a place where people despise you. Where you are accused of being lazy and shiftless after the evidence of your hard work was destroyed by the agents of the people who now despise you.

How do you NOT experience that as what we’d now call trauma? The trauma of ethnic cleansing. Some would say genocide.

The Big Upheaval — what a minimizing euphemism THAT word is for the events the ancestors endured from 1755 to 1763.

But, since it happened about 275 years ago, does it still matter? Has enough time passed to heal wounds and forget about it? If you don’t talk about it, does it disappear?

Seems to matter to other humans who collectively endured like traumas — 400 years ago (enslavement, land grabs from indigenous peoples), 160 years ago (U.S. Civil War), 80 to 100 years ago (World Wars, Holocaust, dropped nuclear bombs on Japan), or in the now (Ukraine-Russia, Israeli-Palestinian wars). The answers, when I think about how people from these collectives talk about the ongoing harms they endure, would be “yes, it matters. And, no, not enough time has passed to forget it.”

Then what happened to disappear awareness of the harms heaped on Acadians?

GKillick on YouTube

I want to understand the consequences of ethnic cleansing of our Acadian ancestors without blaming or shaming. I think of the metaphor of someone slamming a car door on my finger. I’d try not to blame or shame them for doing that, but my finger would still hurt and need healing once the door was opened.

The compelling drive to understand now comes from the surprise sorrow I felt in response to cousin Nicole Gallant Nunes’ latest project: to enumerate by name each of the Acadians who died due to the Grand Dérangement.

Nicole: My big project this summer was to highlight all the key facts about the 765 Filles du Roi in Quebec and it was really a test for this much bigger project that I've had in mind for a while: to list our Acadian ancestors and cousins who were lost.

Well lost isn't really the right word is it?.. since it almost sounds unintentional or accidental...but they were murdered. It was genocide.

We often stumble across their names while researching our family trees and perhaps some of us pause for a moment to reflect and make note of them. Maybe we dig deeper into their lives to learn about their specific story but it's really just us descendants and cousins who do that. The majority of the rest of the world has no idea that this brutality existed for our people. I know this list will end up being thousands of names so it will need to be released in parts but it's a start on a long road to honor them all. I've always felt like I had to do something to bring light into this darkest part of our history. It's that pull that I can't quite explain.

I know there have been some descendants, like myself, who have made these memorial lists for their own families, which is amazing, but I found the information is all spread out. At first it surprised me that no one had compiled all of these names before, but then realization hit of how daunting of a task it is, especially to do it alone, but it would be incredibly powerful to see all of these names, dates and locations in one place. A virtual memorial to those taken too soon. I think the real impact will come when everyone sees the ages. Children.....babies.

It's haunting and heartbreaking and maybe that's part of the reason why this isn't talked about more, but it is SO important. They meant something, everything, to their loved ones who carried their spirits with them through the generations, and they mean something to us now. To be named and spoken of is to live on. If we can honor them in this small way, then we must.

Tell me you aren’t now shedding a few tears yourself.

Nicole asked our Facebook collective to send in the names of people we knew about in our individual family lines — to make sure, as best as possible, no one is forgotten.

Forgotten. How is it that THAT word reached straight into my heart?

Deportation by Acadian artist Patsy Cormier

By sending out the first two lost names I could recall, I left the realm of historical reports. These were no longer among the vague images of “thousands died,” but the once living, breathing, loving, funny, irritable members of my family.

They were real people resurrected in my historical fiction-in-progress: Marie Theotiste Vigneault, sister of my ancestor, at age 11 dying alone and apart from her family on November 13, 1755 in Quebec City. Her maman — Agnes-Anne Poirier — dying probably in Massachusetts sometime between 1758 and 1763. But in which town and how — unknown.

Before the deportation, they lived in Beaubassin. On October 13, 1755, 269 years ago today, the residents of this isthmus were deported on seven ships that left Chignecto for exile to the southern colonies.

I knew these as facts. But I hadn’t felt them so personally until Nicole shifted the lens from those who survived to those who perished. I grieved them. I wondered whether I was becoming a little nutty.

But Nicole also found herself shedding tears as she added names to the list.

So if I’m nutty, at least I’m not alone. There is solace in that.

Then it hit me: We are the empathetic witnesses for our Acadians ancestors, are we not?

Resources